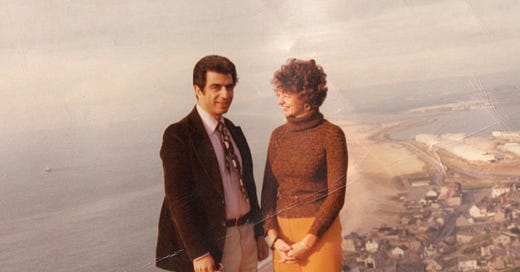

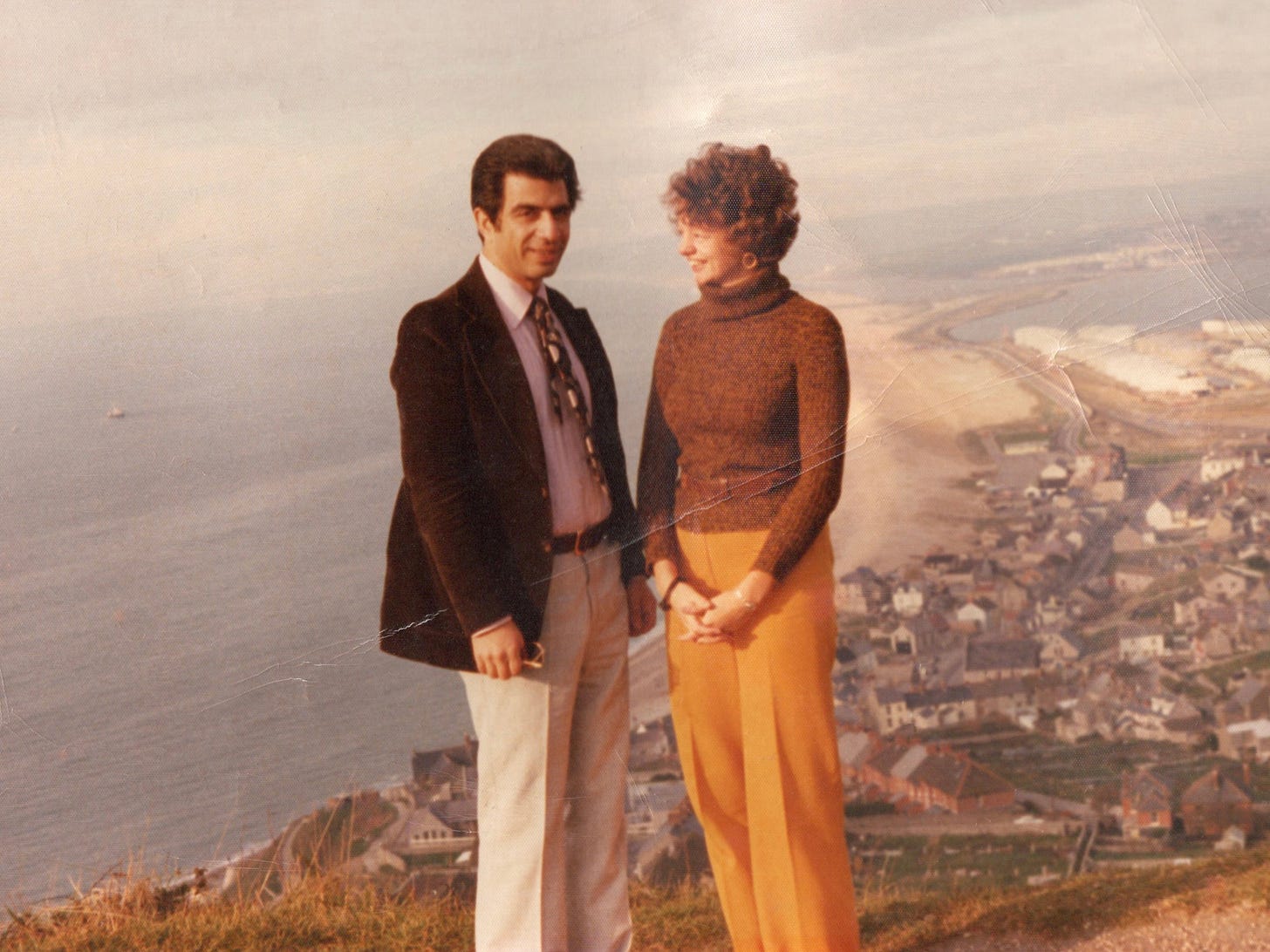

My mum first saw my dad in 1975 at Weymouth Hospital. She was a trainee nurse and he was an orthopaedic doctor, recently transferred from Iran. She glimpsed him through the door of his office: he was on his knees with a dustpan and brush, sweeping up the debris of a cast he’d removed. How compassionate he looked in that moment, how unlike the consultants that talked down to her. And how handsome. A few days later she was leaving work and found him getting into his car with a colleague, and he offered her a lift. She sat in the back, and as he drove he continuously looked up at the rear-view mirror, where her gaze had been waiting to meet his.

I recently immersed myself in those days while making a video for a piece of music that features my dad reading and translating old Iranian poetry, our third such collaboration. I edited the video from super-8 footage that Dad filmed obsessively back then, and which as kids we would watch projected onto the bedroom wall. The video begins with their wedding at the old Bridport registry office in January 1976. Dad is wearing a cream suit and floppy black bow tie, Mum a purple wool ensemble that has inspired admiration in female friends over the years. There is footage of their first flat in Weymouth, and a trip to Windsor Castle with my mum’s brother. But the clip I find most moving shows one of Dad’s first visits to the thatched cottage where my mum’s parents lived, owned by the dairy farm where my grandfather worked. There’s an improbable shot of Dad teaching my gran to do press-ups beside the vegetable patch. Later we see them on West Bay promenade, walking arm in arm, behind them a glimpse of the sandstone cliffs that played a totemic role in my childhood, and which feature on the cover of this record.

The video ends with the pair of them in Iran, where they moved soon after the wedding. Mum had never been before – it was her second trip abroad – but she looks confident as she stands with her glamorous new family in the courtyard of the Tehran home where my father grew up, everyone dressed as though for dinner and handing out elegantly wrapped presents. Dad takes a moment to dance for the camera in the arm-snaking way I would come to know so well. Both of them look happy, filled with excitement for the future opening up before them.

The last shot is of me as a baby, clinging to my dad as he sits astride a horse in a desert town somewhere outside the city. I was born in September 1978. Four months later the Shah took his last flight from Tehran, and Khomeini returned to claim the spoils. We stayed on for a year after the revolution, eventually returning to the UK, where Dad took up jobs in various hospitals before finally settling in Maidstone.

My siblings and I grew up in a pretty un-Iranian home. There was a haft-sin table at Nowrooz, and Iranian food of course, kebabs and stews and rice topped with crispy tah dig that wowed my friends. But we didn’t learn Farsi, and we didn’t talk much about Iran. We had returned in 1984, at the height of the Iran-Iraq war. The visit was fraught with tension, and every evening my dad would drive us to a safe house in the desert to avoid Iraqi bombing raids, telling my younger brother and I that nightly storms were ravaging the city. I think in the wake of that trip Dad was trying to let go of the Iran he still thought of as home, to accept that his future lay in the UK. But the decision haunted him, and I could sense his sadness on pre-dawn drives to Dorset, when he would listen to Iranian cassettes while his family snoozed around him. His favourite singers were by then in self-imposed exile in LA, their hearts broken, their once infectious pop songs replaced by laments for the lives they had lost. I would sit in the back, captivated by the emotion in that music.

I started learning Farsi in my early twenties, and made my first trip back to Iran with Dad in 2004. The following year I returned for three months on my own, staying with my grandmother in the same house that features in the video, the once-grand furnishings now tattered, the cupboards filled with moth-eaten evening dresses and dusty suitcases stickered from distant holidays. Mama, as we called her, was by then in her nineties, and had lived alone since my grandfather died in 1980. She spent her days on a hospital bed in the brightly lit reception room, occasionally holding up a handheld mirror to watch the television that blared constantly behind her (it never occurred to me to ask why she didn’t move the television). She taught me Farsi the same way she had taught my mother decades before: by sending me to the shops with lists of things to buy. In the evenings I would sit in my dad’s old bedroom and listen to his records, rediscovering songs I remembered from those childhood drives, finding in those moments the sound I had been searching for in the music I was beginning to make back in London.

Mama passed just before Covid, and the house was demolished to make way for a block of flats, though it remains a pile of rubble due to paperwork problems. Dad is frail these days, but he is desperate to return. I’ve not been to Iran for a couple of years, and I pine for it daily, though I’m also aware that I have a romanticised view of the place, very different to those who grew up in the shadow of the regime.

It’s something I’m reminded of regularly by Faraz and Malahat, a husband-and-wife kamancheh player and singer who moved to London from the northern sea city of Rasht a few years ago. Playing with them has been the privilege of my musical life, and in stripped back piano sessions I have felt myself dissolve in that uniquely Iranian ocean of sorrow that first captivated me in the car. In those moments I have found a place for my feelings of grief and helplessness at the horrors unfolding in the Middle East, my fear that Dad will live to see war return to his homeland.

But in making this video, and seeing my mum and dad young and in love, I experienced something else: a feeling of lightness and hope for a world in which two people from such different places could embrace and be welcomed into each other’s respective cultures, and so keep this world going in its unfathomable way.

This is a gorgeous piece of writing.

This is a beautiful. Love across time, countries, cultures, generations...